Arnoud Apituley, Marijn de Haij, Steven Knoop, José Dias Neto, Wouter Knap, Pepijn Veefkind, Diego Alves Gouveia, Christine Unal

Information in Dutch can be found here.

The Netherlands had its sunniest March on record with on average 250 hours of sunshine, marked by high pressure and clear skies present over Western Europe for much of the month. However, the weather on Wednesday, March 16 was significantly influenced by the cloud of Saharan dust that was carried over Europe and arrived over the Netherlands that day. At the end of the morning the blue sky disappeared and the sun remained virtually invisible for the rest of the day as can be seen in the photo. At first glance, this seemed to be low clouds, but it was in fact a thick layer of dust that drifted over at a height of about two kilometers. Remote sensing instruments in the Ruisdael Observatory offer great capabilities to observe plumes like these. Equipment at the Cabauw research station and at operational stations in KNMI’s nationwide surface observing network were able to record details of the dust layer. In-situ observations on the ground from the Air Quality Monitoring network and the research instrumentation in Cabauw did not detect high levels of particulate matter.

The influence of dust on the weather is interesting to investigate. Although the presence of the dust was correctly forecasted in models from the Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service (CAMS), the radiation effects were insufficiently taken into account by meteorological forecasting models (HARMONIE). The dust layer of March 16, 2022 blocked so much light that the sun was no longer visible. Scientists call this ‘optically thick’. This has a major effect on the temperature, which was not properly included in the forecasts, because the effects of dust are currently insufficiently calculated. With small amounts of dust, the effect is limited, but a large amount, such as with this event, has a strong influence. Due to the near-complete blocking of the sun, the optical thickness of the dust plume could not be measured by the radiation instruments.

The Sahara dust also has an effect on cloud formation. For example, at the end of the afternoon and early evening it could be seen in Cabauw’s data that light precipitation formed where the dust was in direct contact with clouds. This data will enable researchers to better understand how the properties of the Saharan dust change during transport. The longer the dust is in the air, the composition changes because the larger grains of sand disappear first, and later due to chemical changes.

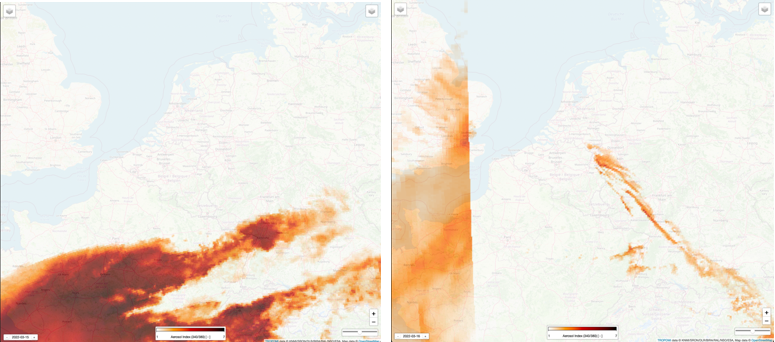

The Sentinel-5p/TROPOMI observations of the UV Aerosol Absorbing Index (UVAI) show the presence of the dust cloud. On 16 March however, it is currently not fully understood how the UVAI values correspond to the ground based observations. This needs further investigation.

The measurements taken on the Saharan dust are the same that allow us to infer the properties of volcanic ash. Thus, this episode provides data to do research on that subject.

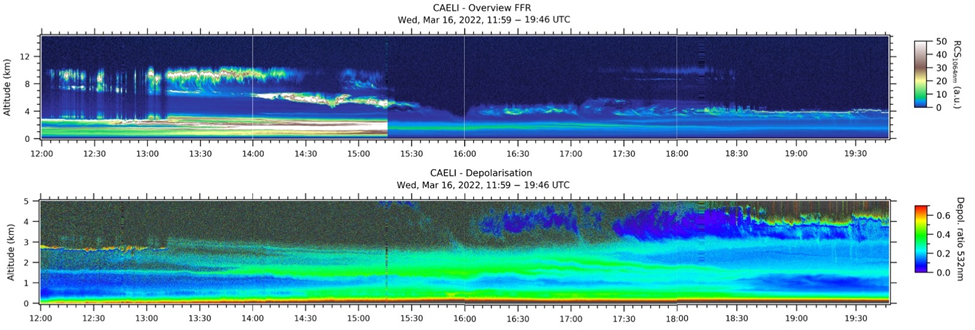

Overview of the KNMI Caeli Raman lidar in Cabauw. The top panel shows the backscatter signal intensity at 1064 nm. The apparent discontinuity in signal strength at about 15:15 UTC is due to the placement of an additional attenuator. The Saharan dust caused so much backscatter that the signals had a tendency of overloading a detector. The lower panel shows the depolarization ratio, that is a measure of particle shape. The Saharan dust particles are of mineral origin and have irregular shapes and show high depolarization ratios. Cloud droplets are more spherical and show low depolarization. After 18:30 UTC some low clouds are forming that are in direct contact with the dust close to 4 km altitude. Aged Saharan dust is known to be hygroscopic and has an effect of triggering precipitation. In the lidar observations, some fall streaks of light precipitation can be seen. At this time, only a few isolated drops reached the ground. The optical properties derived from the Raman lidar data of the dust and clouds are now under investigation (Arnoud Apituley, Diego Alves Gouveia, KNMI).

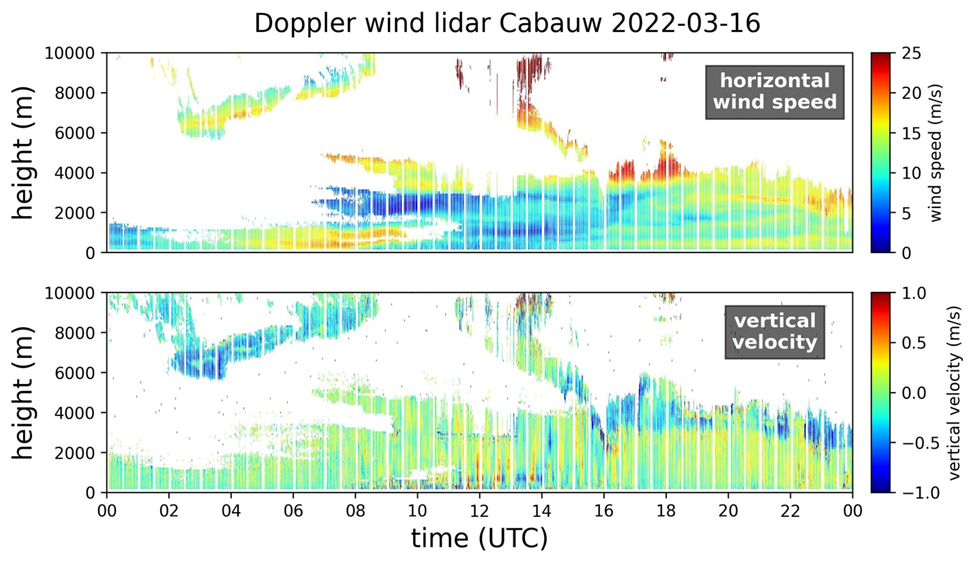

Windprofiling data from the Windcube 200S Doppler wind lidar, showing the horizontal wind speed (upper panel) and vertical velocity (lower panel). For the Saharan dust event it provides dynamic information and together with the classification from the CAELI Raman lidar insight in the interaction between the clouds and the dust. For instance, the negative vertical velocity (downdrafts) from 16:00 UTC on the top of the aerosol/cloud layer may indicate precipitation induced by the dust (Steven Knoop, KNMI).

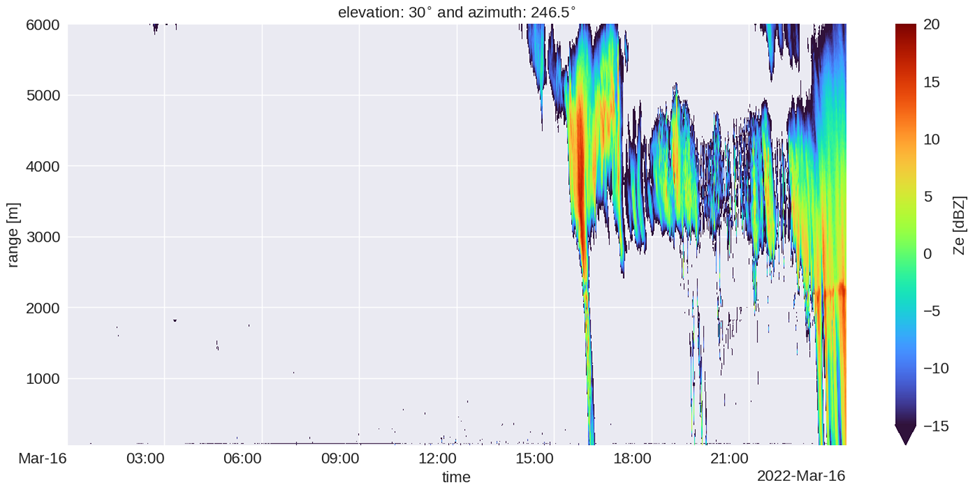

The radar attenuated reflectivity from the TU-Delft 35 GHz cloud radar CLARA in Cabauw. The radar data corroborates the lidar observations of particle growth at the times and places where the Saharan dust is in interaction with clouds. In the radar data, dust (aerosols) is not directly visible (Christine Unal, José Dias Neto, TU-Delft).

Observations of the UV-Aerosol absorbing index (UVAI) from Sentinel-5p/TROPOMI on 15 March 2022 (left) when the dust plume was South of The Netherlands and 16 March (right) when the plume was over The Netherlands. The consistency with the ground based observations needs to be further investigated (Pepijn Veefkind, KNMI/TU-Delft).

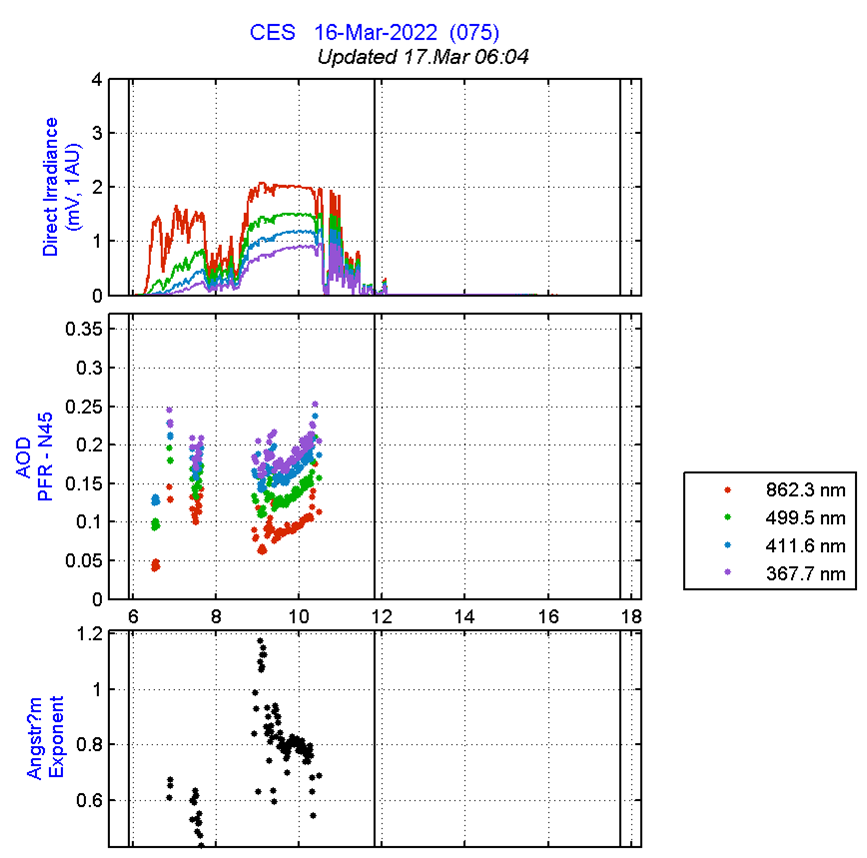

Radiation observations from Cabauw showing the dimming of the direct incoming solar irradiation (top panel). The aerosol optical depth increases (middle panel) but cannot be (automatically) retrieved after about 10:30 UTC due to lack of sunlight. The bottom panel shows information about the colour dependency of the properties of the aerosols, also up to the time when the light is too dim (Wouter Knap, KNMI).